President-Elect Donald Trump has suggested, with the stated purpose of reducing undocumented immigration and drug trafficking, a 25% trade tariff on goods from Canada and Mexico as part of his Trump Tariff Plan. He also suggested an additional 10% tariff on goods from China (current tariffs are 25-100% depending on the import), citing fentanyl trafficking as the motivation.

Tariffs, basically just trade taxes, can be an effective way to raise revenue and add teeth to global policy. However, they are often criticized as being an overly blunt instrument that creates as many problems as it solves.

There is no one-size-fits-all attitude toward tariffs. In fact, Trump’s proposal raises interesting questions. Might there be a benefit to factoring “new” products into tariff discussions? Software is a major export, valued at almost $300 billion. Should nations start putting a trade tariff on software products?

The Problem with Tariffs

Like any major policy, tariffs walk a thin line between effective and senseless. More than 17 million jobs, and almost one trillion dollars in trade would be influenced by Trump’s proposed North American trade tax.

That doesn’t mean that the policy is wrong in its own right. It does mean that the risk/reward proposition is high.

At face value, 25% of one trillion dollars is a big figure.

But that’s not how it works. When tariffs—particularly big tariffs of the sort that Trump has proposed—take effect, prices go up. When prices go up, spending goes down. When spending goes down, jobs are often lost.

There’s a reason the phrase “trade war,” often comes up in the same conversation as tariffs.

That’s not to say that tariffs are always a disaster. In 2018, while Trump was in office for the first time, the United States placed a 25% tariff on Chinese steel. The stated reason was “national security.” China stood accused of overproducing low-quality metal products, which subsequently flooded U.S. markets.

Consequently, United States manufacturers ramped up production of steel creating more jobs, and domestic revenue.

Granted, this also made the price of steel go up, a cost that was inevitably passed onto the consumer in the form of more expensive cars, homes, etc. Still, the 2018 steel tariff is generally viewed as a success.

That’s not always how it goes though.

In 2019, also during Trump’s first term, the United States was at odds with the EU concerning the Boeing Airbus subsidy. The specifics of the disagreement are complicated, and not pertinent in this context.

Here’s what happened: The U.S. placed a 25% tariff on EU exports—particularly wine, cheeses and liquor. Granted, these are specialty products that fall into the discretionary or luxury spending.

Still, the tariff resulted in higher costs for U.S. businesses. Expenses went up and no significant benefits were realized.

None of this is to say that tariffs could not be leveraged effectively on software products in theory. However, there are laws specific to digital technology that may interfere with any effort to impose significant trade taxes on tech products.

Overview: The State of Trade with Software

To date, there have never been any major trade tariffs that focused on software. This owes to several factors:

Software products are generally viewed as intellectual property.

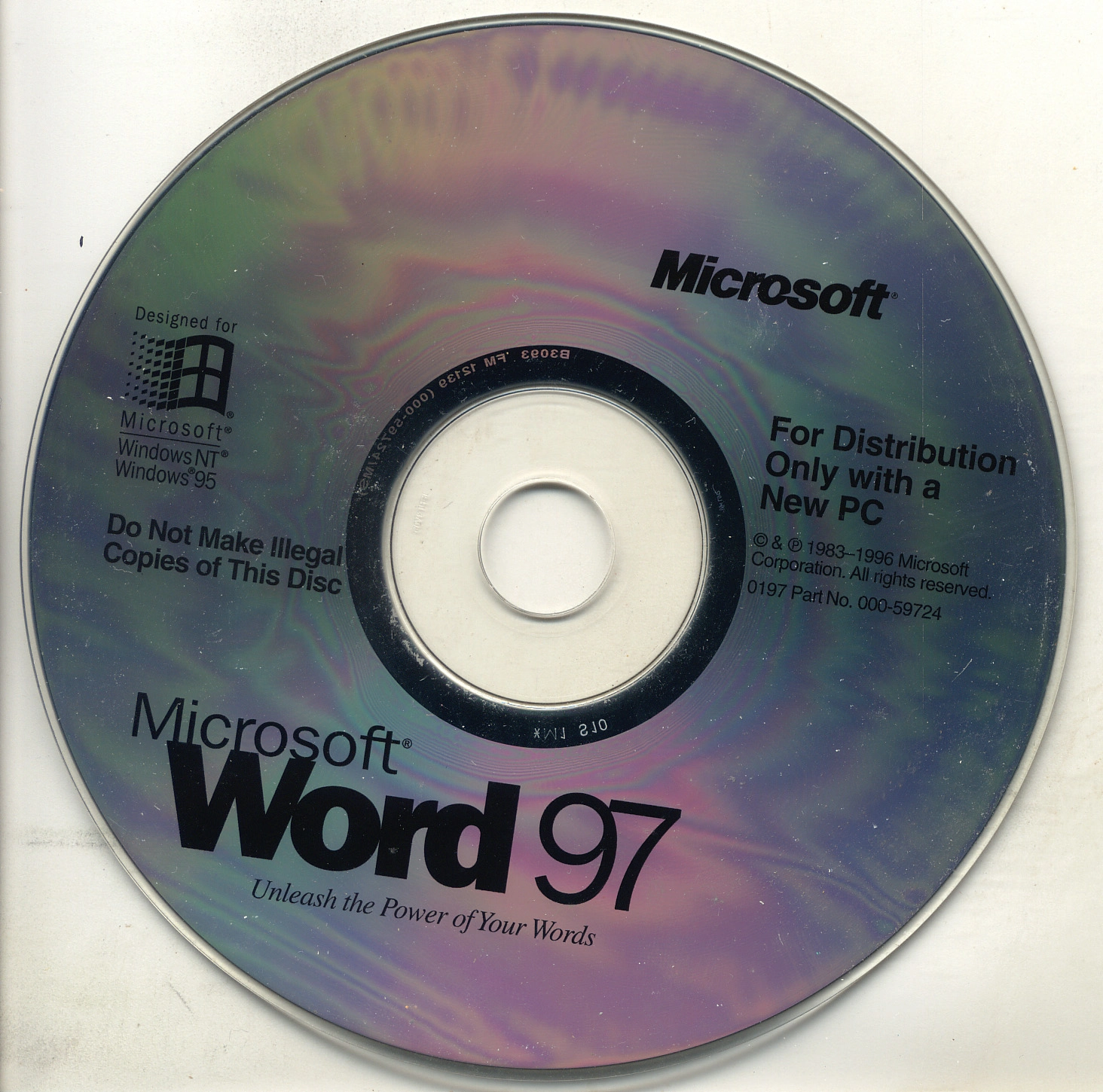

Like a book or a song—any monetized idea rather. Prior to the digital era of software distribution, back when you could buy Microsoft Word on discs, the conversation was slightly different. Even back then, software tended to be classified as media from a trade perspective. Like a DVD or a CD, the value was not on the physical item itself, but the licensing fees.

WTO’s IT Agreement

In 1996, the World Trade Organization signed an agreement to eliminate trade tariffs on many tech products, including software. That agreement was expanded in 2015 to be even more comprehensive.

The goal of the WTO agreement was to make global trade more expansive. World trade agreements are legally binding, but that’s not to say they are strictly followed. Countries are constantly modifying their trade policies, and often these modifications bump up against agreements established by the WTO.

That said, it is not likely that any major global economies will be introducing trade policies that blatantly disregard the 1996 agreement.

That doesn’t mean countries can’t modify their tax law to generate more software-related revenue.

The Digital Service Tax

A digital service tax (DST) is pretty much what it sounds like. Tax revenue generated by the trade of digital products. There are many examples of this throughout the world, one of the most notable currently taking place in France.

At the time of writing, France has a 3% digital service tax on the use of digital services within its border—though there is a proposal to increase that figure to 5%.

How does this tax differ from a trade tariff? A DST will focus on use over providence. It functions more like a sales tax—though it does still target the manufacturer. For example, let’s say Hypothetical Software Company (HSC) provides its product at a fee of $100 per year.

The French government would take 3% of that action resulting in $3 out of every sale. In theory, it’s revenue taken from the business. In practice, the costs are often passed onto the consumer.

The thinking behind a DST is that people/businesses spend a lot of money on software (e.g. video conferencing)—revenue that floats beyond borders as if on a (pun-intended) cloud. With this specialized tax, the French can keep more of their money within its borders.

DSTs are not exactly a tariff, but they do generate trade revenue in a similar way.

Looking forward

Should countries consider implementing tariffs on software? Violating WTO agreements—though not unheard of, is a bad idea. Still, with software products being a global enterprise, legislation like the French DST policies could be attractive for countries all over the world.

Software generates a lot of money. Tax strategies designed to circulate that cash within a nation’s domestic borders could make a lot of sense.

The devil lies in the details. A heavy-handed 25% tax—regardless of how or why it is applied—would be incredibly disruptive and expensive for consumers. The gentler policy currently leveraged by the French offers a moderate alternative.